Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: esplanade theatre, lemi ponifasio, mau, tempest without a body, theatre

How do we stage the primitive? How do we enact violence? These are critical questions to be addressed in considering Lemi Ponifasio’s Tempest: Without a Body, the production which has attracted one of the most polarising reactions at this year’s arts festival. While some members of audience have been most profuse with their compliments, there are those who absolutely hated it, with walk-outs happening as early as fifteen minutes into the show.

Most of the flak were directed towards what was seen as a gratuitous sensory assault, at times tending towards audience abuse. Others decried its apparent lack of meaning, denouncing it as an overblown aesthetic excursion. Both accusations puzzle me, less so due to the justifications provided – which I must say contain a ring of validity -, but the vehemence with which they are articulated. After all, there are a good many other productions at the festival which are equally, if not more vulnerable towards such indictments, and none of them have attracted dislike of such extent.

The reason for this perhaps lies in the sheer baggage of expectations that Tempest had to contend with, most of which were simply not fulfilled. For one, the title carries a heavy literary reference and I would not be surprised if anyone had walked in expecting to see a re-interpretation of the Shakespearean classic. Other references in the programme notes – “post-911”, “Giorgio Agamben”, “institutional injustice”, “terrorism” and “colonialism” – farther suggests an engagement with prevailing political discourses, when discursivity is perhaps the one thing that Ponifasio eschews.

Interestingly, it is the reference that I feel was the least discussed that singularly defined the performance for me – Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus. Klee is a fitting source of inspiration in many ways, for the works of the painter-aesthetician are similarly bold experiments that come with subdued and thus all the more unsettling political undertones.

In Angelus Novus, we see a monster which Walter Benjamin has once described as “the angel of history”. There is something bewitching about this grotesque semblance of an angel, particularly with its sphinx-liked countenance and its head of unfurling scrolls that resembles Medusa’s. Its wings are spread out, but appear locked in stasis. The angel is suspended not in flight, but in limbo. Its gaze is averted away from the viewer, disregarding the present while fixated with an invisible time-space that Benjamin described to be that of history. Its beastly jaws are open, but the viciousness of its snarl is deflated by the tiny fangs that stick out rather lamely. It is an image of surrender, of a hapless angel stupefied by the vistas that it encounters as it is propelled away by the winds of change.

Like in Tempest, the political undercurrents in Angelus Novus are perceptible, but they are there not to buttress a tedious exegesis of what the work is about, but to be dissolved into the textures that constitutes what the work is. As it seems, both Ponifasio and Klee are artists who do not seek for interpretation as an end-point; instead, interpretation, if necessary at all, is that which enriches experience, meant to farther sensitise us to the sensorial plenitude presented.

This is why one who tries to construe Tempest as a kind of political text must necessarily falter, for this is a work that demands not reading, but direct experience. In this theatre of textures, ominous drones, baroque designs and traumatised bodies dominate, collectively conjuring a haunting yet intensely lyrical world.

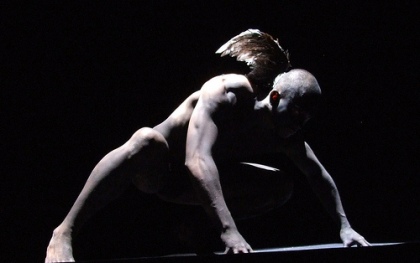

The performance opens abruptly with an acoustic explosion, blaring into our ears a wall of mechanical noises. Upon the stage, a hunched, tottering woman appears, dwarfed by a massive, vertical wall with a rock-like surface that is suspended from the ceiling. She appears to be an angel, but the tiny wings that spurt out of her back like vestigial appendages make her look more like a monster. She cannot fly, for the wings that are usually the embodiment of freedom are upon her an ugly deformity. Her body is soiled with dirt, her face ghoulish and the scream that she howls pained and chilling to the bone. This recurring image of the ravaged angel-monster is one of the show’s most startling, and the first of the many traumatised bodies that follow.

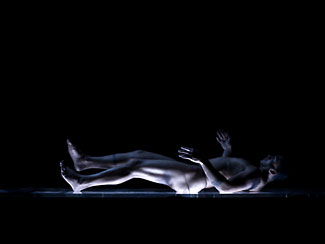

Later, a naked, supine body is seen wobbling across a raised platform. He appears not to be moving at his own whim, impelled instead by the onslaught of spasms that run through the length of his torso like a malevolent current. Here, we see the interplay of light, colour and body at its most ingenious. Against the coarse texture of the towering wall, the man appears like a gleaming sapling of a being, with the reflected sheen taking on a surreal purple-grey hue due to the paint on the body. This subtle colouration of the body, seen also in the other performers, is one of the most delicately devised features of the show. Against the inky blackness of the stage, these tinted bodies gain a spectral translucency that suggests their gradual disappearance. The colour is also striking for its reminiscences of the paintings of Francis Bacon, in which the very same hue appears upon the coagulated, deoxygenated bodies that too, lie like pieces of carcasses upon an improvised plinth of sorts.

This connection with Bacon, I believe, is more than serendipitous, for in its portrayal of violence, Ponifasio has created what Deleuze, in writing on the paintings of Bacon, called the “violence of sensation”, and here, I find no better way to convey the nuances of this notion than to quote directly from the author himself:

What fascinates Bacon is not movement, but its effect on an immobile body: heads whipped by the wind or deformed by an aspiration, but also all the interior forces that climb through the flesh. To make the spasm visible. The entire body becomes plexus. If there is feeling in Bacon, it is not a taste for horror, it is pity, an intense pity: pity for the flesh, including the flesh of dead animals…

It is the confrontation of the Figure and the field… that rips the painting away from all narrative but also from all symbolization. When narrative or symbolic, figuration obtains only the bogus violence of the represented or the signified; it expresses nothing of the violence of sensation (emphasis mine) – in other words, of the act of painting.

Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation by Gilles Deleuze

The precision with which Delueze’s text can be applied upon Ponifasio’s work is almost uncanny. Indeed, the bodies that populate the stage have been stripped of their capacity for symbolisation. They do not perform, represent or signify violence but are, simply put, the very incidence of it happening. The presence of these diminutive bodies upon the vast cavern of the stage is itself a point of resistance, as each solitary figure wrestles with space that presses upon his body-space. Whether is it the four-legged beast who restlessly circles the stage against an unruly soundscape of barking dogs, or the hefty, heavily-tatooed man who stands solemnly like a bulwark protecting the Maori tradition, the bodies we encounter all remind us of their vulnerability to the surrounding elements. Their movements are prolonged, repetitive and at times Butoh-like, as if their bodies are in pereptual negotiation with the forces acting from within and without them.

Meanwhile, in counterpoint to these slow-moving, traumatised bodies are the fleet-footed men in black who frequently glide into the stage to enact a set of highly controlled and ritualistic gestures. With their synchronised thigh-slapping and hurried shuffling of feet, these bald, monk-like men come across as a squad of lifeless automatons. Could they possibly, just possibly, signify the bureaucratic colonisers?

Indeed, it would be doctrinaire to consider Tempest as a pure experience devoid of all potential for signification. There are certainly many possible ways to read the performance if one wants to. For one, the distinctive Maori elements already point towards a potential post-colonial discourse. The work could also very well be a larger, more encompassing examination of human history, with the suspended wall construed as a civilisational mural that bears the marks of its vicissitudes.

But these possibilities for signification, I believe, must remain just that – as pure possibilities; insinuations that serve to intensify our experience of the performance’s textures, without reducing them to mere devices for aiding interpretation.

In fact, it is when the performance tries to do the latter, when it tries to interpret itself, that it slightly comes apart. The sequence in which the tatooed man reappears in a corporate suit to delivering a blistering speech against the Christian invaders, for instance, is far too direct, even jarring against the general abstraction of the piece. Other parts such as when the squad of automatons begin to hurl chucks of plaster against a helpless man, creating a massive cloud of white dust; or when the angel-woman tries to use the fallen dust to wash herself, are far too reminiscent of the old-fashioned clichés of purgatory and redemption.

Notably, it is when the performance consciously tries to invoke that the power of its expression becomes lost.

In my conclusion, I turn once again to Deleuze. On the figures on Bacon’s paintings, he said:

These are monsters from the point of view of figuration. But from the point of view of the Figures themselves, these are rhythms and nothing else, rhythms as in a piece of music, as in the music of Messiaen, which makes you hear “rhythmic characters”.

The monsters of Ponifasio’s universe are precisely that: rhythms – rhythms of terror and paralysis that nonetheless manage to animate the senses and expand the power of theatre.

Ho Rui An